It is perhaps surprising, given the iconic visual imagery of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, that only a handful of American feature-length adaptations exists: David Fleischer’s rotoscoped Gulliver’s Travels (1939), Jack Sher’s live-action The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960), Charles Sturridge’s miniseries, Gulliver’s Travels (1996) and, most recently, Rob Letterman’s 3D movie, Gulliver’s Travels (2010). These four adaptations may initially seem vastly different. Fleischer’s film is a children’s animated tale; Sher’s, predominantly a moralistic love story; Sturridge’s is both an adventure tale and a psychological drama; and Letterman’s film is a farcical children’s comedy. What might these adaptations have in common, besides the name of their central character? And which film, if any, comes closest to successfully rendering Swift’s tale on screen?

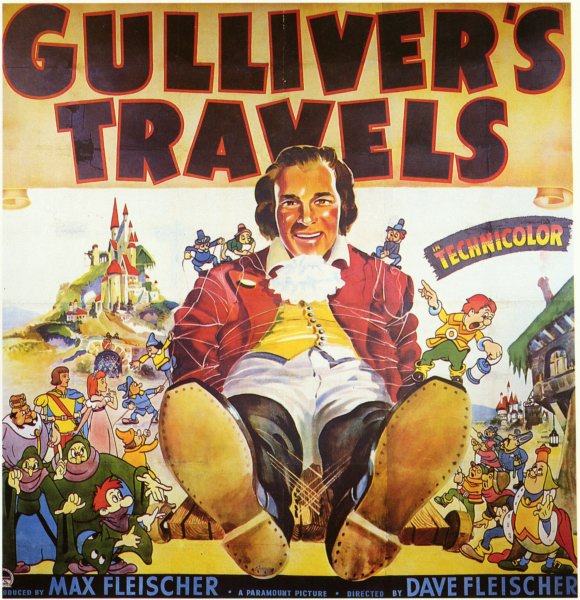

Gulliver film adaptations predominantly share two qualities: reliance on the latest technology in visual effects, relatedly, and the prioritization of spectacle over plot. While the latter is certainly influenced by the visual nature of Swift’s detailed descriptions, it is also a reflection of the possibilities of film as a visual medium. The very first adaptation of Gulliver’s Travels demonstrates the advantages of film technology in telling a fantastical tale like Swift’s. Produced in 1902, Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants sets the precedent that most adaptations follow, using cutting-edge film techniques to play with scale in Lilliput and Brobdingnag. If we are to measure an adaptation’s achievements by its representation of impossible worlds alone, we might see each movie as a success. Fleischer’s studio invented rotoscope animation, which traces live-action film sequences in ink, blending Gulliver’s rotoscoped body with traditionally animated Lilliputians. The promotional poster for The 3 Worlds of Gulliver boasts of its use of “Superdynamation,” a stop-motion animation process that allows Gulliver to interact with Lilliputians. Sturridge’s miniseries makes dazzling use of CGI effects, and Letterman’s film combines CGI with Hollywood’s technological trend du jour, 3D.

With the exception of Sturridge’s miniseries, these visuals represent a limited scope. Fleischer, Sher, and Letterman each make movies that adapt only part of Gulliver’s Travels, essentially depicting a version of the children’s book abridgements made popular by Francis Newbery’s 1776 illustrated chapbook. As with the films, such abridgments focus solely on Part I, and occasionally also Part II, of Gulliver’s Travels. Indeed, it is from abridgements like these that we even have the title Gulliver’s Travels, itself abridged from Swift’s original title, Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. Yet these three films do not only abridge, they also adapt. Adaptation, in the sense of making something relevant for a new or different audience, is crucial for filming a story like Gulliver’s Travels. Rooted in the minutiae of eighteenth-century political satire and social commentary, Swift’s work is not an easily transportable story in its entirety.The question for all four films becomes, which part of Gulliver’s Travels should be adapted: the narrative or the satirical spirit? The answer, it seems, is different for each filmmaker.

Fleischer’s Gulliver’s Travels is content with adapting only the story’s most basic premise:a shipwreck lands Gulliver on the island of Lilliput, where he meets the tiny Lilliputians and resolves their feud with the neighboring Blefuscudians. Fleischer’s goal is clear: to create a children’s movie that rivals Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), from the easily identifiable villain right down to the singing birds that befriend the princess. Fleischer reduces Swift’s story to a simplistic children’s fantasy where the Lilliputians mimic the goofball antics of Snow White’s dwarfs and Disney’s own slapstick Lilliputians from the animated short, “Gulliver Mickey” (1934). Despite Fleischer’s title sequence, which presents a scroll written by Gulliver promising to “give thee a faithful history of my most interesting adventure,” the film is very much from the Lilliputian point of view (an invention of early abridgments of the book). The comedic Lilliputians dominate screen time; Gulliver is unconscious until over a third of the way through the film. He is often nothing more than a mute set piece, drawn as part of the static background upon which the animated Lilliputians move and act. Though Gulliver’s role in the book is a kind of participant-observer, which allows him to evolve throughout his travels, for most of Fleischer’s film, Gulliver is neither participant nor observer, and satire is replaced by juvenile comedy.

The movie focuses on the bickering between King Little of Lilliput and King Bombo of Blefuscu, whose disagreement threatens to prevent the wedding of their children. Even though the reason for dispute differs from the original egg-cracking controversy, the film retains a hint of the narrative’s satirical mode by making the argument equally pointless. The kings cannot agree upon which national song, “Faithful” or “Forever,” should be played at the wedding. Gulliver’s resolution becomes an origin myth for remixers: mash the songs together and sing “Faithful Forever”. This bare-bones plot is filled in with singing, dancing, and humorous sequences such as the Lilliputians tying Gulliver to the ground, an extended scene that looks like a Silly Symphonies cartoon. These elements firmly situate Fleischer’s Gulliver within the children’s movie genre and indicate that Fleischer adapts not Swift’s tale, but Newbery’s abridgment and others like it. Thus, if we view Fleischer’s Gulliver’s Travels as an adaptation of Swift’s Gulliver, it fails. If we see it instead as adapting abridged versions—which themselves have rich print histories—the movie succeeds in portraying the simplified, children-friendly fantasy of a giant man in a tiny world.

Over twenty years after the release of Fleischer’s film, Jack Sher’s The 3 Worlds of Gulliver premiered in 1960. The title indicates the Sher’s abridgment, limiting Gulliver’s journey to three destinations: Lilliput, Blefuscu, and Brobdingnag. To call these locations “worlds” rather than “nations” suggests each place is imagined or an alternate reality. The movie distances the locations from the real world, which often severs their ties to the very real country they satirize in Swift’s work. Sher rectifies this issue at the end of the film. Gulliver (Kerwin Mathews) and his fiancé, Elizabeth (June Thorburn), who inexplicably travels with him to Brobdingnag, wash ashore in England, uncertain if their past adventures were real or a dream. Elizabeth asks, “What if the giants come back?,” to which Gulliver responds in the film’s most Swiftian sentiment, “They’re always with us, the giants and the Lilliputians, inside us. They’re a terrible world waiting to take over our lives. Waiting for us to make a mistake, to be selfish again.” Gulliver’s comment universalizes Swift’s satire on British politics. Not content to end on Swift’s pessimistic note, however, Sher chooses to conclude with a message of hope. When Elizabeth asks, “How can we bear it? How can we live with such fear?,” Gulliver answers with a response that held cultural ground throughout the rest of the 1960s: “With love.”

Sher’s Gulliver is not so much an ethnographer as he is a preacher, and his unyielding morals drive the plot. Gulliver decides to stay in Lilliput, for example, because he’d like to change their world into “a land without greed or envy, where no man has an enemy.” His ideas about a vice-free society sound more like discoveries he should make in Houyhnhnm Land than in Lilliput. In addition, Gulliver is often portrayed as Christ-like, presenting the Lilliputians with an endless supply of fish and suffering mistreatment by the emperor by replying, “I stop wars; I put out fires, feed people, give them hope and peace and prosperity. How can I be a traitor?” It is likely that Gulliver’s insistence on love and equality is a reflection of the year the movie was produced. Several scenes seem to satirize the Vietnam War, such as Gulliver’s condemnation of the Brobdingnagians, “What you don’t understand, you want to destroy,” and his plea to the emperor of Lilliput, “I am not an enemy. I’m only different.” (The emperor tellingly responds, “That’s the same thing, Gulliver.”) Despite the film’s more brazen liberties with Swift’s text, most notably the introduction of Elizabeth and her and Gulliver’s strange marriage scene in the Brobdingnagian court, Sher effectively evokes Swift’s satirical spirit, adapting it for a new political and social context.

Unlike Sher, Charles Sturridge’s adaptation directs focus to the narrative. His two-part miniseries for Hallmark Entertainment is the only American adaptation to portray all four parts of the original text. Sturridge presents Gulliver’s Travels as an Odyssean drama: Gulliver (Ted Danson) leaves England for nine years. While he is away, his wife (Mary Steenburgen) is pursued by a new character named Dr. Bates (James Fox), and Gulliver’s son struggles with feeling abandoned by his father. This new narrative strain functions as the framing device for the film. When Gulliver returns home, he must try to mend his relationships with his family, despite the meddling of Dr. Bates, who forces Gulliver into a mental institution. The set-up feels melodramatic, but presenting Gulliver in Bedlam is a fascinating way to extrapolate his position at the end of Swift’s tale. Problems arise, however, when the film suggests Gulliver is not institutionalized because of his presumed mental instability, but rather to allow Dr. Bates to court Gulliver’s wife. This motive loses sight of Gulliver’s experiences abroad, redirecting the drama to family issues at home. In addition, this framing device means that Gulliver must only return home once, at the very end of his adventure. Why would Gulliver, straight from Houyhnhnm Land, even bother explaining Lilliput or Laputa to a bunch of yahoos? Why doesn’t he immediately retreat to the stable? The movie never quite resolves this contradiction, sticking to Swift’s order of events while eliminating Gulliver’s first return to preserve this new frame.

In addition to the smaller problems the framing device creates, the frame gives the film its biggest inconsistency with the text: the ending. Like Sher before him, Sturridge gives Gulliver a hopeful resolution. Unlike Sher, however, Sturridge provides this resolution even after showing Gulliver’s realization that he is a yahoo. Despite Gulliver’s transformation in Houyhnhnm Land, he is relieved to be proven sane when his son presents a Lilliputian sheep to the court, and the movie closes on a scene of familial reunion. The villainous Dr. Bates is conquered. Gulliver, who pleaded with Bates with uncharacteristic remarks like, “I need to see [my wife]. I know she’ll understand if I can only see her and explain,” is vindicated. Yet, his vindication is not about proving the existence of Lilliput or the Houyhnhnms but about happily returning to his family. At the end of Swift’s tale, by contrast, Gulliver can barely tolerate eating dinner with his wife across a long table, and he stuffs his nose with leaves to avoid her yahoo smell. The contradiction here is embedded in the film itself. Gulliver’s last line, in a sullen voiceover, is, “I see myself for what I truly am.” He doesn’t finish the sentence with, “a yahoo.” The ambiguity of the statement, when overlaid with the image of Gulliver and his family, means viewers can finish that sentence with a happier “a husband,” “a father,” or even simply, “a man.” In short, Gulliver recovers, a reprieve that Swift was not so willing to grant.

Sturridge’s framing technique is not without its merits, however. The frame’s present-tense interweaves with Gulliver’s recounting of past travels, often blending the two creatively. One particularly effective instance is the discovery of Gulliver’s unconscious body in Lilliput. A Lilliputian father and son stumble upon Gulliver, and as the son says “Oh my God, Dad, look!” the camera pans up Gulliver’s unconscious body to reveal Gulliver’s own son standing over him asleep in the barn. These blended moments create nice connections between Gulliver’s travels and his home life, but these parallels aren’t quite satirical like Swift’s. Rather, they focus on themes like father-and-son relationships. The most Swift-like interweaving is near the movie’s end, when present-day Gulliver enters a medical courtroom for a sanity hearing and past-Gulliver arrives at Houyhnhnm Land and encounters his first Yahoos. The alignment between the sniveling, bureaucratic doctors and the wild Yahoos is the film’s best satirical moment.

Occasionally these interwoven scenes seem to implicate Gulliver as mentally unstable, rewriting his words not as a past event but as a present delusion. When Gulliver cuts vegetables with his son, he suddenly spies a Lilliputian emerging through the table. His son asks, “What are you looking at?” and Gulliver responds, “Shh! The emperor is demanding my presence!” The scene muddles the viewer’s sense of time. Are we watching scenes of Gulliver’s past experiences, or are we watching his present delusions? Sturridge’s film focuses on whether Gulliver’s travels were real, at the expense of exploring the satirical meanings and purposes behind those travels.

When the movie does study Gulliver’s experiences abroad, though rarely uninterrupted by the sometimes intrusive framing narrative, Sturridge’s storytelling excels. The film’s 187 minute runtime allows Sturridge to cover far more ground than previous adaptations. Gulliver visits Lilliput and Brobdingnag, the popular destinations in other versions. He also encounters the floating island of Laputa, the island below it, Balnibarbi, meets the academicians of Lagado, a sorcerer in Glubbdubdrib, several struldbruggs, and finally, the Yahoos and Houyhnhnms. Within each of these adventures, the visual design, from costumes and sets to intricate CGI effects, bring the fantasy to life more successfully than any adaptation before. Within these sections of the film, narrative changes are small, and the film’s faithfulness to Swift’s detail is particularly impressive. The architecture of Gulliver’s Lilliputian house, the stars and musical instruments on the Laputians’ robes – these subtle but accurate aspects add to the movie’s visual achievements. Sturridge’s miniseries covers the most narrative ground, possesses the most visual detail, and displays some effective moments of satire. As an adaptation of Gulliver’s Travels, it is the most successful of these films.

It is fitting to conclude with a review of Robert Letterman’s Gulliver’s Travels, not only as it is the most recent adaptation, but also because it borrows so heavily from each of the adaptations that came before it. Letterman’s film was billed as a big-budget vehicle for comedian Jack Black. The movie, like Fleischer’s and Sher’s, is an abridgment, set predominantly in Lilliput with a brief trip to Brobdingnag. It is the only American feature-length adaptation to place the narrative in present time; the Lilliputians discover not Gulliver’s pocket watch but his iPhone. Black’s Gulliver is the quintessential slacker. An underachieving, unhappy mailroom worker, he tells his new colleague, “We are the mailroom guys. Mailroom guys are meant to be seen and not heard. And ideally not even seen, OK? We are not on their level. We are the little people.” When Gulliver gets his first opportunity to write a travel essay in the Bermuda Triangle, a freak storm lands him on the Lilliputian shore, where, for once, he feels important. He can save Lilliput from “Blefuscian” attack; he is, as the film repeatedly reminds us, not so “little” anymore. Giving Gulliver the chance to be a travel writer is a subtle nod to Swift’s original text, presented as a satirical addition to the popular travel narrative genre. Other small references to Swift’s tale emerge, from an imprisoned Gulliver’s refusal to eat hay (a wink to Houyhnhnm Land), and the gravity-defying architecture of Gulliver’s Lilliputian home (suggesting Laputa), to the film’s closing credits, which roll over a collage of Gulliver’s travel writings about Houyhnhnms, Laputa, and Brobdingnag. Letterman and Black gleefully include Gulliver’s fire dousing via urination, a scene from Swift that only Sturridge had shot before. Tellingly, this is perhaps the only specific plot point from the text that makes it into Letterman’s film. Here, however, Gulliver’s action is not grounds for treason; rather, it but makes him an even greater hero to the Lilliputians. This eighteenth-century scatological humor seems to suit Black’s style of comedy. For instance, he cannot avoid a joke about Gulliver’s giant rear end, and the visual gag (in 3D, no less) plays out like that of a popular William Hogarth print, “Punishment Inflicted on Lemuel Gulliver,” which made a similar joke hundreds of years earlier.

These allusions suggest that, despite the farcical comedy of Jack Black, Letterman’s movie is well aware of its source material. The film simply chooses to ignore most of it. Letterman’s Gulliver is less an adaptation of Swift than it is an adaptation of other versions of Gulliver. As such, the plot is relatively sparse, as the film is more interested in hitting every iconic visual marker of Gulliver’s Travels than actually following Swift’s tale. Letterman’s romantic subplot regarding the Lilliputian princess (Emily Blunt) posits Gulliver as a royal matchmaker, a role taken similarly in Fleischer’s film. Also like Fleischer, Letterman emphasizes the Lilliputians’ impressive building skills, although, in addition to building intricate restraints for Gulliver, Letterman’s Lilliputians build things such as giant coffee makers and Guitar Hero controllers. It’s all visual gag, no substance. Letterman perhaps directly references Fleischer when the Lilliputians build a contraption to decorate Gulliver’s shirt with the medals of a general. The scene is strikingly similar to the structure Fleischer’s Lilliputians build to dress Gulliver in a new coat.

Letterman’s movie adapts some elements of Sher’s The 3 Worlds of Gulliver as well. Like Sher, Letterman gives Gulliver a romantic interest who joins him on his adventure. Here, it is Darcy (Amanda Peet), a travel writer, who follows Gulliver to Lilliput. Both films’ heroes desire to prove themselves and feel important. Sher’s Gulliver wants to prove he can provide for his future family. Letterman’s Gulliver wants to impress a girl; the stakes have lowered. While Sher’s Gulliver ultimately decides “the only safety is in being obscure and being nothing,” Letterman’s Gulliver revels in turning Lilliput into a shrine to himself, complete with billboards bearing his likeness. This Gulliver does not learn humility; he only learns to secure his popularity by actually doing the heroic things he claims he can. This devolves quickly into an underwhelming Transformers sequence, when Gulliver faces off with a Blefuscian robot controlled by rebel Lilliputian, General Edward (Chris O’Dowd). O’Dowd and Blunt, it should be noted, are the best things about this adaptation. Aware that their characters are satirized fools, both play their parts with over-the-top gusto that pokes fun at the Lilliputians. They provide the satire. Black is too busy convincing his new friends to call him “President the Awesome” and strumming air-guitars. He is essentially a big kid, which becomes explicitly clear when he turns a host of Lilliputians into his personal Star Wars action figures. Gulliver’s immaturity takes center stage. Despite the plethora of allusions to Swift and other adaptations, the movie ultimately falters due to its relentless emphasis on Gulliver as an overgrown buffoon.

What Letterman’s film shares with each of the other three movies, however, is absolute dedication in portraying three key scenes: Gulliver tied to the Lilliputian beach, Gulliver standing as Colossus, and Gulliver capturing the Blefuscudian fleet.These moments, while no doubt memorable in Swift’s text, become iconic first as illustrations and then as visual set pieces. Gulliver’s Travels was illustrated almost immediately after it was published, with the first English illustrated edition appearing in 1727. Scenes like these also appeared in Newbery’s abridgment, which seems to have determined not only what parts of the narrative readers would most encounter for generations to come, but also which passages were the most visually interesting and deserving of illustration. As each film adaptation takes so many visual cues not from Swift’s descriptions but from popular illustrations it seems that these films build themselves from the visual culture surrounding Swift’s narrative. These movies never adapt some ideal, isolated version of Swift’s text, but always a tangible book in which the tale is printed.Thus, we see traces of maps, prefaces, abridgments, and especially illustrations, in each film adaptation we encounter. One visual medium borrows from another. Both film and illustration continue to portray Swift’s tantalizingly imaginative world that one just has to see to believe.

Works Cited

The 3 Worlds of Gulliver, directed by Jack Sher. Columbia Pictures, 1960.

Gulliver’s Travels, directed by Dave Fleischer. Fleischer Studios, 1939.

Gulliver’s Travels, directed by Rob Letterman. Twentieth Century Fox, 2010.

Gulliver’s Travels, directed by Charles Sturridge. Hallmark Entertainment, 1996.

Swift, Jonathan. Adventures of Captain Gulliver. London: F. Newbery, 1776.

—. Travels into several Remote Nations of the World, in four parts. By Captain Lemuel Gulliver. London: Cooke, 1795.

—. Travels into several Remote Nations of the World, in four parts. By Captain Lemuel Gulliver. J.J. Grandville, illustrator. London: Haywood and Moore, 1840.